Ramli Ibrahim (all pics below courtesy of Ramli Ibrahim)

In this 11 March 2010 interview with The Nut Graph in Petaling Jaya, Ramli talks about his staunch yet fluid Malay-ness, and his desire for a Malaysia that can be comfortable with its own diversity. A fuller version of this interview was published exclusively in Volume 1 of Found in Malaysia.

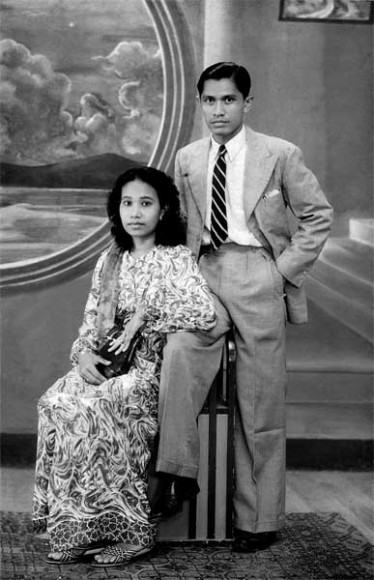

Ramli's parents

Ramli Ibrahim: I was born in Kajang, on 20 May 1953, and brought up in Kuala Lumpur.

Where in Kuala Lumpur did you grow up?

I grew up in Jalan Pekeliling, which is now Jalan Tun Razak. I went to the Pasar Road Malay School and then to the infamous Cochrane Road School, where all the gangsters were, then to the Royal Military College (RMC), and then to Australia.

I didn’t do my “O” levels but did my matriculation. I was the earliest of the Mara (Bumiputera Council Trust) batch of matriculation students who were sent to Perth.

I did my degree in engineering, knowing very well that my eventual destiny would be in the arts as a dancer or in theatre.

Just to digress: I have always been interested in the healing aspect of mak yong. I started delving into mak yong when its public performance was banned in the early 1990. I have looked at mak yong through main ‘teri (from “main petri”).

I am interested in the use of myth to heal the psyche. I am fascinated by the two polarities of personality-types of dewa muda and dewa pechil (dewa terpencil), the extroverted and the introverted in traditional Malay character archetypes found in mak yong and used in healing.

Main ‘teri is a compelling example of how traditional psychotherapy functions through the performance of the tok ‘teri (shaman) who manipulates the metaphors found in these myths to enable him to heal through the release of blocked angin and strengthening of the semangat. The approach found in traditional healing of “unusual sickness” or sicknesses of the mind, is fascinating for me.

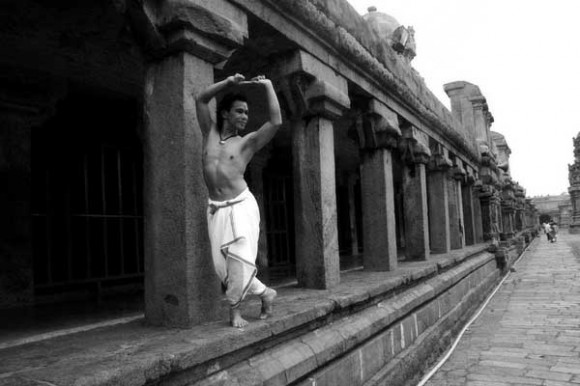

Among a thousand pillars in Tanjavur, India (pic by Karthik Venkataraman)

I was told that my father was from Rawa, Sumatera. My mother was more or less from the Malacca area, or Kelemak. Is there such a thing as “pure Malay”? I don’t know; my mother and grandmother looked a bit Chinese. My father is dark; he could look like a mamak. That has never been a problem for me. Anyway, I’m not into tracing my family tree (yet).

But I think we are as Malay as you can get.

A chubby Ramli, the heart-breaker at two and half years old (1955).

As a child I read Hikayat Malim Deman, and [all the others] in Jawi! My father was a Malay literature lecturer. So we were surrounded by Syair Siti Zubaidah, Sejarah Melayu and the old Malay books. I recited those syairs, and I was even johan syair kebangsaan (national syair champion) in Kuala Lumpur when I was 11. It was only after my remove class that I started to speak English.

There must be a link somewhere between all of this and doing classical Indian dance.

It’s a progression. My mother and father were religious and staunch Umno supporters. My mother was in the Kaum Ibu. I was brought up on that wave of perjuangan. So I am familiar with stalwarts like (Tan Sri) Aishah Ghani. But this is a bygone era — the perjuangan thing is over. It probably died with Tun Ghafar (Baba). I find the present globalised era devoid of the true perjuangan ethos, and there is cynicism when altruism is mentioned, especially in politics.

Are there are any stories from your parents or grandparents that stick in your mind?

My mother always talked to me about the Haw Par Villa (in Singapore): the concept of good and evil, and in neraka how you’re going to be paralysed and potong lidah (have your tongue cut off) and all those things. She terrified me with images of the hereafter.

One of the things she told me as a child that I thought was cruel was that I was a Chinese anak angkat (adopted child) from a Chinese vegetable seller. I found that this is the kind of story every parent tells all the time. They don’t know that this has an incredible effect on their own child.

[…]

But my mother’s stories were character forming. My father was quiet. His influence, not to say that he [did not have] much effect on me, was not the same.

I think eventually the balancing of my anima and animus was important because I am now very comfortable with my anima. It balances my androgyneity, which is important for Indian dance. I tell my students, “If you are a good performer, you have to balance the ‘male’ and the ‘female’ within you.” You have to be almost neutral [so as to] inhabit the character and feel the “rasa”. And especially in Indian classical dance where you have to take on many roles, you have to be quicksilver when making this transformation.

One of the saddest things about the present Malay situation is not being able to understand the energy transforming from one manifestation to another. You cannot pinpoint and say, “This is the only way you can do it.” But the Malays through the introduction to a more patriarchal and Semitic religion, have become literal-minded rather than [exercise] their ability to use metaphors — which they used to be able to do. Now they want only the concrete thing, whereas the real thing is not so easy to grasp.

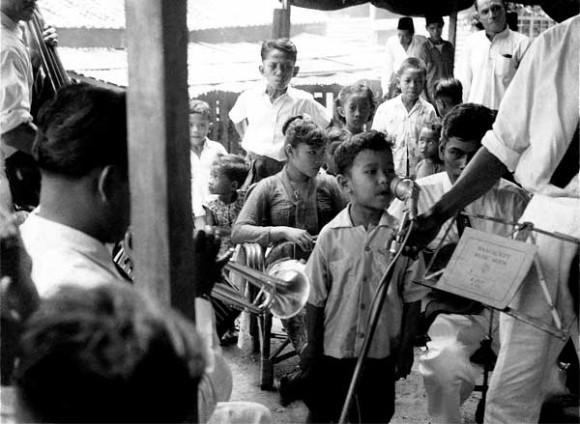

A five-year-old Ramli already showing off as a singer at a wedding function, Kerling (1958)

Whatever happens, I’m psychically connected with this place. I was in Australia for 14 years but was less psychically connected with Australia. I can’t remember much of my time there; except for some performances, nature, or surfing. Whereas in Malaysia or in this region, with India and Indonesia, I have an intense psychic connection.

This where I am. I have been fighting my battle in Malaysia. Come what may, this is where I’m going to be. I see it as a process. Nothing is going to be completely good, but I must have the equanimity to accept it, and be with it and do whatever I can.

But there’s this current debate about what it means to be Malay, “Jangan cabar Melayu,” “Jangan cabar Islam,” — what do you think of all this?

Look, I do Indian classical dance because I find it’s one of the most challenging and difficult art forms for solo [dance]. In that sense I’ve always been a global person, because I am into all the best that [the world] can offer. At the same time, I’m very nationalistic. I don’t like it when I see mak yong, main petri and wayang kulit being banned. I think they’re the best of Malay traditional pastimes that we have.

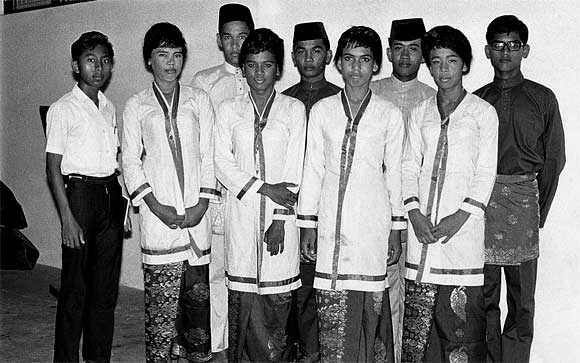

Ramli (in songkok), a “freshie” at RMC, roped in to do the Malay joget. Back row (left), 1969

The people who [truly] champion Malay culture now are not necessarily Malay. We go back to being Malaysians. And Malay culture is part of Malaysian culture. So now there are non-Malays championing makyong or wayang kulit. They also champion Chinese opera and Indian classical dance. They see it as, “The richer we are in culture, the better.”

What about the politicians who say, you cannot challenge this or that, this is what it means to be Malay.

I think the Malays have got their own insecurities. Having said that, life is not easy. That’s why the mak yong has a tendency to identify with the dewa pechil, or dewa terpencil. Dewa pechil is a Malay archetype. He is complex as he is very sensitive. But when he leaves, the nation is bereft of “seri”. He is the kind of person who always merendahkan diri, (appears) to want to be in the background. This is one aspect of the Melayu that I find endearing, and at the same time exasperating. Not pushy, very accommodating, affectionate and loving.

And I think the Malays have always been in between the entrepreneurial races, with the Chinese on one side and so on. It’s difficult now to make a shift to being tough, because it is against the grain. But it can be done. It is a complex problem: how do we balance this?

Ramli, the trendsetter, modelling the sarong during a university student function

It’s hard to find a solution — the problem lies in the nation’s psychic make-up which is not homogenous and cannot be measured quantitatively in profit and loss. It’s one of the complex human dramas which can be alluded to in an artistic manifestation, in literature, film or theatre. That’s why art is so important as a moderator and as an agent of understanding that brings about change of the nation’s psyche.

So then what kind of Malaysia do you want to see?

I want to see Malaysians only. The generations of non-Malays are fully Malaysians, [as are] Malays also. Malays now are changing, especially the urban ones. But we don’t know what the non-urban ones are thinking because there has been insecurity there. The ketuanan Melayu thing, the religious upbringing, the madrasah, the indoctrination through Friday khutbah, is happening on different and subversive levels. And this is indoctrination from young. It’s not a homogeneous society.

I think Malaysia has to resolve her issues about Malaysian-ness. How this process [will] be brought forward is going to be difficult, because Malays will feel like they are losing something, whereas they are already losing a lot.

For example, when it comes to religion, I think one of the worst things is what fundamentalist Islamism has done to women [and] to men. We don’t want this kind of fanatical and rigid Islam. What do you think? What I’m saying is true, isn’t it? That kind of Islam is a regression — it’s the worst that could befall us.

No comments:

Post a Comment