WHATEVER you may think about him, Perkasa president Datuk Ibrahim Ali is found in Malaysia, too. The Nut Graph gets a glimpse into what shaped this combative right-wing politician during an interview in his Kuala Lumpur office on 10 Aug 2010.

Ibrahim, who is also independent Member of Parliament for Pasir Mas, talks about the childhood poverty that fuelled his years as a student activist and then as a politician.

TNG: When and where you born, and what was your childhood like?

TNG: When and where you born, and what was your childhood like?

Ibrahim Ali: I was born on 25 Jan 1951 in Kampung Pasir Pekan in Tumpat, Kelantan. I am the fifth child and eldest boy of 13 children. Because I was the first boy, my father pampered me a lot. But nothing luxurious. We were a poor family, and one of the things I did as a child was to plant watermelons to supplement the family income.

Our house was near a river which had a small island in the middle of it. I planted watermelons there. Now the area has been reclaimed and there’s a Tesco hypermarket there.

My childhood friends who were non-Malay [Malaysians] included a lot of Siamese kids because there was a Siamese community in my area. We did a lot of fishing and also meluba ikan, where you use a pail to catch fish by scooping them out of the water. We also went on picnics. There weren’t many Chinese; in school I had five or six Chinese friends.

Tell us about your ancestry and what your parents were like.

My ancestry on both sides is pure Kelantanese, but we might also have had some relations with Thailand. As you know, Pattani, Songkhla, and Narathiwat were historically owned by Kelantan before they were given to the Thais after a war.

My father was the village head. He was uneducated, but known as a brave and influential man. As village head, he was in charge of security and had to handle a lot of crime as we were near the Thai border. He received a small salary but it wasn’t enough for our large family.

My father would take me with him everywhere he went for his village-head duties. We would ride on his motorbike, and we would go out so often and for so long that sometimes he would quarrel with my mother over this. And because I was the village head’s son, sometimes there were people who made sure I didn’t have to walk – if I was going somewhere, there would be people who took turns to carry me on their shoulders all the way until I arrived.

When I was older and doing Form Six, my father was arrested under the Public Order (Preservation) Act 1958 for being a strong PAS supporter. The late Tunku Abdul Rahman also offered him a post in Umno Youth, which he rejected.

As for my mother, she was very pious. She was the one who taught us about Islam and to be committed to it.

What aspects of your childhood do you think have shaped you into the person you are today?

What aspects of your childhood do you think have shaped you into the person you are today?

Observing my father as a village head. The culture of helping other people is what motivated me into student activism in my college years, and later, into politics. Being poor and facing hardship also made me rebellious.

I did not like the fact that I had to travel for so long to get to school, and when I arrived there, I saw the children of wealthy families being dropped off in cars or in paid trishaws. I had to first walk 15 minutes from my house to the river, then take a boat for 45 minutes to an hour, and then walk another half an hour to school.

I also would not get new school clothes or shoes for a long time. I had only one school shirt which was washed and hung to dry after school to wear again the next day. One pair of school shoes had to last three years before I got new ones.

To earn some money, I would sometimes bring two or three of my watermelons to school – as many as I could carry – borrow a knife from the canteen to cut them up, and sell them to my friends for a few sen a slice.

I also helped my father with the cultural shows he organised. He would erect a fence made of coconut leaves in our kampung, call in a wayang kulit troupe, and I would be the one collecting money for the show. Twenty sen per entry. He also organised Thai boxing and dikir barat shows, and sometimes our family would be able to make a small profit.

In primary school, I was class monitor from Standard One onwards. I also studied in different primary schools. First it was Sekolah Kebangsaan Padang Mandul, then Sekolah Kebangsaan Pasir Pekan, and then an English primary school in Tanah Merah, which was in another district. I moved because my parents couldn’t provide for such a big family, so I was sent to live with my uncle. I spent my secondary school years in Sekolah Kebangsaan Islah.

I did Lower and Upper Six in Maktab Abadi, a private school, where I couldn’t afford the fees, but they allowed me to work part-time while studying. They also allowed me to live underneath the school – it was a building on stilts, so I used plywood to make a kandang structure and I lived there. After Form Six, I signed up to do a Bachelor of Laws (LLB) in Institut Teknologi Mara (ITM), although later I switched my course to Mass Communications instead.

You mentioned being a student activist. What were your experiences?

I came to Kuala Lumpur by train to go to ITM with just RM10 in my pocket. I had no idea where ITM was. Luckily, when I walked over to Masjid Negara from the train station, I saw an ITM bus. There was some programme going on at the mosque. So I tumpang the bus back to the Shah Alam campus. It was in ITM that I became involved in student activism.

I was close to (Datuk Seri) Anwar (Ibrahim) during this time. I first met him while I was in Form Six when he came to my college to speak. He was already a student in Universiti Malaya (UM) then, and he was president of the National Union of Malaysian Muslim Students (PKPIM). At that time in college, I was president of the Muslim Students’ Association of Kelantan. That’s how our paths crossed. I met Anwar again in ITM during orientation.

After my first semester in ITM, I became secretary-general of Kesatuan Siswa ITM. Later I became its president. I was also elected deputy president of two student groups: PKPIM and the National Union of Malaysian Students. This was in 1972, the time of many student demonstrations. We demonstrated over all sorts of things – the situation in our colleges, against the Universities and University Colleges Act 1971, and for ITM to be made a university.

After my first semester in ITM, I became secretary-general of Kesatuan Siswa ITM. Later I became its president. I was also elected deputy president of two student groups: PKPIM and the National Union of Malaysian Students. This was in 1972, the time of many student demonstrations. We demonstrated over all sorts of things – the situation in our colleges, against the Universities and University Colleges Act 1971, and for ITM to be made a university.

On 22 April 1974, we organised 6,000 ITM students to do a protest march from Shah Alam to Parliament. Over 1,000 were arrested, and quite a number injured and hospitalised. It was crazy! ITM closed for a month.

Things cooled for a while, but in December 1974, we demonstrated again over mass poverty in Baling (in Kedah). The price of rubber had dropped and the farmers there were facing starvation. There was one family who was so poor, all they had to eat was some kind of ubi, which turned out to be poisonous, and they died. It happened that at the time, the National Union of Malaysian Students had a project called “Desa Siswa” in Baling, so we were there when the incident happened. We organised a demonstration there of 10,000 people.

After coming back to KL, we continued protesting at Dataran Merdeka, asking the government to raise rubber prices. It was a two-day demonstration. Anwar joined on the third day, when the protest had moved to the national mosque.

That day, police started arresting people. I was arrested together with Anwar and put in the red police truck. But it was so packed inside that the door wouldn’t hold – it opened and I was right by the door. Everybody inside jumped out and escaped. Anwar and I ran and hid in a temple along Jalan Bandar. He was affected by the tear gas. I found him a taxi and sent him home, while I went back to Dataran Merdeka to see what was happening. Police were arresting more students. Later, I heard that Anwar was also arrested. I went to Port Klang for a few days to lie low.

I was arrested when I decided to go back to the Union House near Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia to get some belongings. I rode a motorbike there, and it looked like everything was fine. In the Union House were seven or eight people who appeared to be sleeping. I thought they were students. But no, they were Special Branch! They were waiting for me. So 11 of us were arrested under the Internal Security Act. Nine were released after 60 days.

I was first taken to the police station near Odeon Cinema, and then transferred to the police station on Jalan Bandar. Anwar was already here. I faced intensive interrogation, almost 20 hours a day. After 60 days, two top-ranking officers said to me, “We have charges against you – you are a threat to the country’s security.” If I remember correctly, there were 21 charges. And they said I could be freed if I signed a confession. They said the other detainees had already signed confessions. I asked them if Anwar had signed his, and they said no. I said, if Anwar didn’t sign it, then I won’t, either. That’s how I came to be in Kamunting for two years.

Why were you so enraptured with Anwar?

Why were you so enraptured with Anwar?

I was idealistic and Anwar was my idol. He was such a great orator and he had great commitment and passion. I went to Kamunting because of him! If not, I would have signed the confession paper.

In Kamunting, I stayed with Anwar in the same block, Block 8. We ate our meals together, talked, played badminton. I also completed the final year of my Mass Comm degree in Kamunting.

Anwar was released three months before me. When I came out, we were both invited by the Saudi Arabian government to attend the World Assembly of Muslim Youth. This was 1976. After the conference, I stayed back to travel all over the Middle East. After Pakistan, I came back to Malaysia. I was offered jobs, by (then Information Minister) Tun Ghazali Shafie to be an information attaché at the United Nations, and by (then Finance Minister) Tengku Razaleigh Hamzah at Petronas, but I turned these down. I wanted to open a private professional school for external courses. I borrowed money and started the Kuala Lumpur Polytechnic in 1978.

What or who is a Malaysian to you?

A Malaysian to me is a one who puts loyalty to the King first as he is the symbol of the nation, and then one who abides by our federal constitution. That’s all. That to me is a Malaysian.

What kind of future do you want for Malaysia?

I want to see Malaysia continue as a peaceful country where people of different races live happily. And there should be economic balance among the races. By that, I am talking about the 30% stake, which is the objective of the New Economic Policy. Once we achieve this, I’m fine. I might not even raise bumiputera issues anymore once we achieve this. I accept everyone as Malaysian.

But the majority of those who are backward are still Malay [Malaysian]. All I want is to see the 30% objective met.

Ibrahim, who is also independent Member of Parliament for Pasir Mas, talks about the childhood poverty that fuelled his years as a student activist and then as a politician.

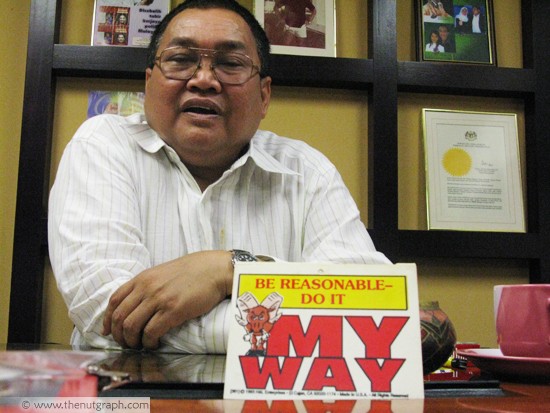

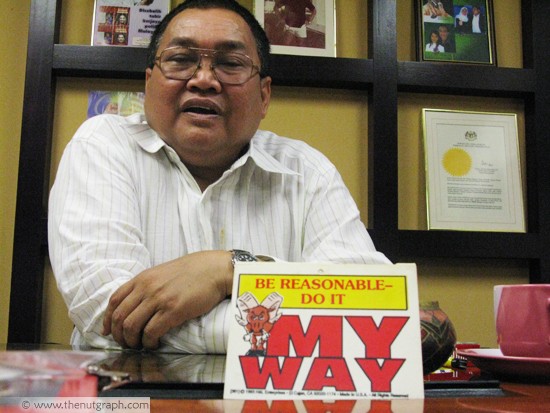

Ibrahim in his office with a sign that says much about his politics (All pics below courtesy of Ibrahim Ali)

Ibrahim Ali: I was born on 25 Jan 1951 in Kampung Pasir Pekan in Tumpat, Kelantan. I am the fifth child and eldest boy of 13 children. Because I was the first boy, my father pampered me a lot. But nothing luxurious. We were a poor family, and one of the things I did as a child was to plant watermelons to supplement the family income.

Our house was near a river which had a small island in the middle of it. I planted watermelons there. Now the area has been reclaimed and there’s a Tesco hypermarket there.

My childhood friends who were non-Malay [Malaysians] included a lot of Siamese kids because there was a Siamese community in my area. We did a lot of fishing and also meluba ikan, where you use a pail to catch fish by scooping them out of the water. We also went on picnics. There weren’t many Chinese; in school I had five or six Chinese friends.

Tell us about your ancestry and what your parents were like.

My ancestry on both sides is pure Kelantanese, but we might also have had some relations with Thailand. As you know, Pattani, Songkhla, and Narathiwat were historically owned by Kelantan before they were given to the Thais after a war.

My father was the village head. He was uneducated, but known as a brave and influential man. As village head, he was in charge of security and had to handle a lot of crime as we were near the Thai border. He received a small salary but it wasn’t enough for our large family.

My father would take me with him everywhere he went for his village-head duties. We would ride on his motorbike, and we would go out so often and for so long that sometimes he would quarrel with my mother over this. And because I was the village head’s son, sometimes there were people who made sure I didn’t have to walk – if I was going somewhere, there would be people who took turns to carry me on their shoulders all the way until I arrived.

When I was older and doing Form Six, my father was arrested under the Public Order (Preservation) Act 1958 for being a strong PAS supporter. The late Tunku Abdul Rahman also offered him a post in Umno Youth, which he rejected.

As for my mother, she was very pious. She was the one who taught us about Islam and to be committed to it.

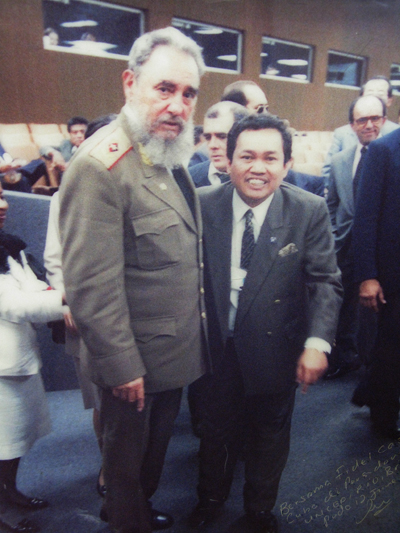

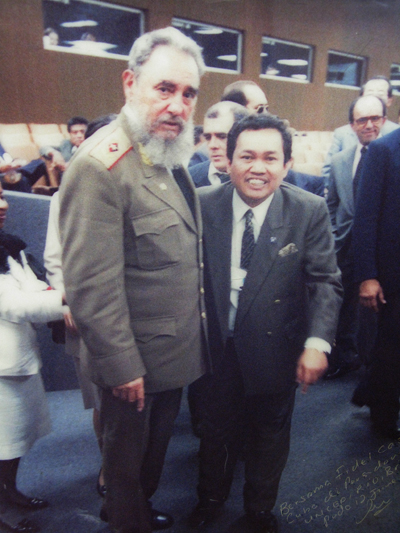

Ibrahim meeting then Cuban president Fidel Castro in Brazil in 1992 at the Earth Summit

Observing my father as a village head. The culture of helping other people is what motivated me into student activism in my college years, and later, into politics. Being poor and facing hardship also made me rebellious.

I did not like the fact that I had to travel for so long to get to school, and when I arrived there, I saw the children of wealthy families being dropped off in cars or in paid trishaws. I had to first walk 15 minutes from my house to the river, then take a boat for 45 minutes to an hour, and then walk another half an hour to school.

I also would not get new school clothes or shoes for a long time. I had only one school shirt which was washed and hung to dry after school to wear again the next day. One pair of school shoes had to last three years before I got new ones.

To earn some money, I would sometimes bring two or three of my watermelons to school – as many as I could carry – borrow a knife from the canteen to cut them up, and sell them to my friends for a few sen a slice.

I also helped my father with the cultural shows he organised. He would erect a fence made of coconut leaves in our kampung, call in a wayang kulit troupe, and I would be the one collecting money for the show. Twenty sen per entry. He also organised Thai boxing and dikir barat shows, and sometimes our family would be able to make a small profit.

In primary school, I was class monitor from Standard One onwards. I also studied in different primary schools. First it was Sekolah Kebangsaan Padang Mandul, then Sekolah Kebangsaan Pasir Pekan, and then an English primary school in Tanah Merah, which was in another district. I moved because my parents couldn’t provide for such a big family, so I was sent to live with my uncle. I spent my secondary school years in Sekolah Kebangsaan Islah.

I did Lower and Upper Six in Maktab Abadi, a private school, where I couldn’t afford the fees, but they allowed me to work part-time while studying. They also allowed me to live underneath the school – it was a building on stilts, so I used plywood to make a kandang structure and I lived there. After Form Six, I signed up to do a Bachelor of Laws (LLB) in Institut Teknologi Mara (ITM), although later I switched my course to Mass Communications instead.

You mentioned being a student activist. What were your experiences?

I came to Kuala Lumpur by train to go to ITM with just RM10 in my pocket. I had no idea where ITM was. Luckily, when I walked over to Masjid Negara from the train station, I saw an ITM bus. There was some programme going on at the mosque. So I tumpang the bus back to the Shah Alam campus. It was in ITM that I became involved in student activism.

I was close to (Datuk Seri) Anwar (Ibrahim) during this time. I first met him while I was in Form Six when he came to my college to speak. He was already a student in Universiti Malaya (UM) then, and he was president of the National Union of Malaysian Muslim Students (PKPIM). At that time in college, I was president of the Muslim Students’ Association of Kelantan. That’s how our paths crossed. I met Anwar again in ITM during orientation.

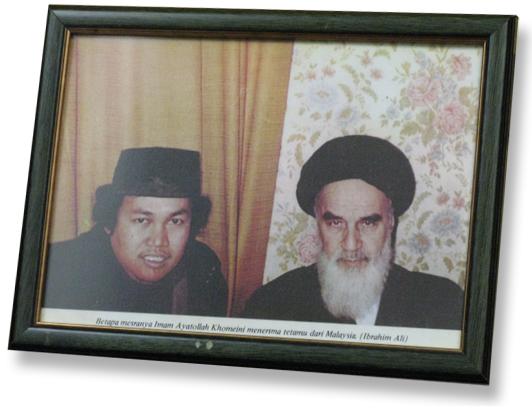

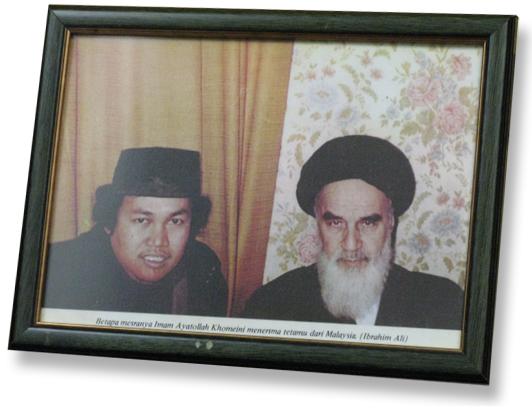

Meeting Ayatollah Khomeini in Paris in 1978

On 22 April 1974, we organised 6,000 ITM students to do a protest march from Shah Alam to Parliament. Over 1,000 were arrested, and quite a number injured and hospitalised. It was crazy! ITM closed for a month.

Things cooled for a while, but in December 1974, we demonstrated again over mass poverty in Baling (in Kedah). The price of rubber had dropped and the farmers there were facing starvation. There was one family who was so poor, all they had to eat was some kind of ubi, which turned out to be poisonous, and they died. It happened that at the time, the National Union of Malaysian Students had a project called “Desa Siswa” in Baling, so we were there when the incident happened. We organised a demonstration there of 10,000 people.

After coming back to KL, we continued protesting at Dataran Merdeka, asking the government to raise rubber prices. It was a two-day demonstration. Anwar joined on the third day, when the protest had moved to the national mosque.

That day, police started arresting people. I was arrested together with Anwar and put in the red police truck. But it was so packed inside that the door wouldn’t hold – it opened and I was right by the door. Everybody inside jumped out and escaped. Anwar and I ran and hid in a temple along Jalan Bandar. He was affected by the tear gas. I found him a taxi and sent him home, while I went back to Dataran Merdeka to see what was happening. Police were arresting more students. Later, I heard that Anwar was also arrested. I went to Port Klang for a few days to lie low.

I was arrested when I decided to go back to the Union House near Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia to get some belongings. I rode a motorbike there, and it looked like everything was fine. In the Union House were seven or eight people who appeared to be sleeping. I thought they were students. But no, they were Special Branch! They were waiting for me. So 11 of us were arrested under the Internal Security Act. Nine were released after 60 days.

I was first taken to the police station near Odeon Cinema, and then transferred to the police station on Jalan Bandar. Anwar was already here. I faced intensive interrogation, almost 20 hours a day. After 60 days, two top-ranking officers said to me, “We have charges against you – you are a threat to the country’s security.” If I remember correctly, there were 21 charges. And they said I could be freed if I signed a confession. They said the other detainees had already signed confessions. I asked them if Anwar had signed his, and they said no. I said, if Anwar didn’t sign it, then I won’t, either. That’s how I came to be in Kamunting for two years.

In Kamunting detention centre, 1974

I was idealistic and Anwar was my idol. He was such a great orator and he had great commitment and passion. I went to Kamunting because of him! If not, I would have signed the confession paper.

In Kamunting, I stayed with Anwar in the same block, Block 8. We ate our meals together, talked, played badminton. I also completed the final year of my Mass Comm degree in Kamunting.

Anwar was released three months before me. When I came out, we were both invited by the Saudi Arabian government to attend the World Assembly of Muslim Youth. This was 1976. After the conference, I stayed back to travel all over the Middle East. After Pakistan, I came back to Malaysia. I was offered jobs, by (then Information Minister) Tun Ghazali Shafie to be an information attaché at the United Nations, and by (then Finance Minister) Tengku Razaleigh Hamzah at Petronas, but I turned these down. I wanted to open a private professional school for external courses. I borrowed money and started the Kuala Lumpur Polytechnic in 1978.

What or who is a Malaysian to you?

A Malaysian to me is a one who puts loyalty to the King first as he is the symbol of the nation, and then one who abides by our federal constitution. That’s all. That to me is a Malaysian.

What kind of future do you want for Malaysia?

I want to see Malaysia continue as a peaceful country where people of different races live happily. And there should be economic balance among the races. By that, I am talking about the 30% stake, which is the objective of the New Economic Policy. Once we achieve this, I’m fine. I might not even raise bumiputera issues anymore once we achieve this. I accept everyone as Malaysian.

But the majority of those who are backward are still Malay [Malaysian]. All I want is to see the 30% objective met.

No comments:

Post a Comment