If historical pattern of Umno’s revivals after 1990 and 1999 can be of any guide for the future, Umno is now deprived of its first favourable condition: policy or leadership change.

If historical pattern of Umno’s revivals after 1990 and 1999 can be of any guide for the future, Umno is now deprived of its first favourable condition: policy or leadership change.Wong Chin Huat, Fz.com

MANY people will celebrate this coming Saturday as the 6th anniversary of the 2008 Political Celebration.

For Malaysians who want regime change, March 8 is the most commemorative date on the calendar because it gives them hope, or in the words of writer Kee Thuan Chye, it was “the day Malaysia woke up.”

March 8 six years ago was the day the Opposition parties, for the first time after 1969, denied the ruling coalition its customary two-thirds, and first time ever, rule a host of five states. It was the day many Malaysians discovered that their votes actually could make a difference.

But the very reason why March 8 is so widely commemorated by Pakatan Rakyat and Civil Society is also really because they cannot celebrate May 5, the day that is supposed to end Umno’s 59/51 years rule of Malaya/Malaysia.

In other words, every celebration of the greatness of March 8 is an unspoken mourning over the failure of May 5.

So, how many more years will the Malaysia democrats celebrate most grandly the March 8 near-miss because they cannot celebrate regime change?

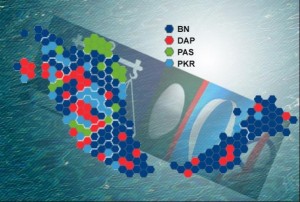

How did Umno/BN rebound from near-misses?

The answer may lie with Pakatan Rakyat: PKR, PAS and DAP.

Lest we forget, 2008 was not the first time Umno and BN escaped their defeat. In fact, it was the third, after the 1990 and 1999 abortive attempts. Each time, Umno and BN bounced back stronger than before.

In both the 1990 and 1999 episodes, three things happened: change – of policy or leadership – in BN; break-up of the opposition coalition; and, seat increase and constituency redelineation.

1. Change in BN Policy/Leadership

Conventionally, the First-Past-The-Post electoral system forces political parties to win the middle ground voters. Hence, electoral set-backs will often lead to change of policy or leadership to restore a party’s popularity or voters’ confidence on it.

BN followed this rule in 1990 when the opposition won 47% of votes, and some 70% support amongst Chinese voters. But it managed to secure majority of Malay voters west of Banjaran Titiwangsa because Tengku Razaleigh wore a Kadazan traditional headgear with a crucifix-like pattern. That became the evidence he sold out the Malay-Muslims to Kadazan-Catholics.

To win back the Chinese voters, within four months from election, Tun Dr Mahathir Mohamad dished out Vision 2020 and introduced cultural and educational liberalisation, which paved way for significant increase in Chinese support of BN for the next three elections.

In 1999, BN secured the support of the Chinese who were largely afraid of another 1969-style post-election riot as well as an Islamic State should PAS come to power. But the Malays were polarised by Mahathir, whose sacking of Datuk Seri Anwar Ibrahim was seen by many Malays as tyrannical and un-Malay.

To save Umno, Dr Mahathir retired on November 2003. In March 2004, his successor Tun Abdullah Ahmad Badawi called a fresh poll and won a 91% parliamentary majority.

2. Break-up of Opposition Coalition

Umno/BN’s revival requires the Opposition coalitions to break-up so that middle-ground voters can be convinced that Umno/BN is the only electable party to run the country.

Some misunderstood that the opposition parties were more disunited than the BN parties. The actual fact is that coalitions are much built by the benefits and prospects of staying in power.

That’s why Umno schisms in both episodes would lead to formation of opposition coalitions which were respectively led by Razaleigh’s S46 and Anwar’s Keadilan.

When the opposition coalitions lost the elections without even denying BN’s two-third majority, the incentives to hold the opposition parties together disappeared.

After 1990, PAS pushed Hudud Law in Kelantan, S46 became more Malay nationalistic, and DAP soon quitted the opposition pact. And PAS and S46 too fought in Kelantan before Razaleigh’s troop rejoined Umno.

After 1999, PAS pushed Hudud Law in Terengganu, while PKR with Anwar in jail couldn’t do much, not long after the 911 Incident, DAP again called it quit.

And of course, disarrayed oppositions made BN naturally appealing, especially after policy and leadership changes respectively.

3. Seat Increase and Constituency Redelineation

While the above two factors are well-known, few realise the BN’s rebound was amplified by seat increase and constituency redelineation in the Peninsula that happened before the next election.

The 1994 redelineation was packaged with an increase of 12 seats in Peninsula, leading to a net of six more seats allocated for Umno to contest.

While Mahathir’s BN was no doubt way more popular in 1995 than in 1990, DAP and PAS were shortchanged in the Peninsula by constituency redelineation.

In 1990, DAP won 20 seats (then 15.15% of the Peninsula’s total) with 18.04% of votes, yielding a vote value of 84%. To get the concept of vote value, think of vote analogously as a bank note, DAP could only get RM 0.84 worth of goods with a RM1 note.

By 1995, its vote share dropped by about one third to 12.13%, but its seat dropped sharply to only 8 (now 5.56%), yielding a vote value of 46%. In other words, the value of a DAP vote was almost halved.

Similarly, despite a slight increase of vote share from 7.79% to 8.45%, PAS found itself still winning only seven seats in a larger pool. The value of a vote for PAS dropped from 68% to 58%.

Abdullah’s 91% parliamentary landslide in 2004 was BN’s largest since Independence but his vote share, 63.85%, was only the second highest. Mahathir bagged the highest vote share of 65.16% in 1995 but only 84.38% of seats.

How did Abdullah do better than his predecessor? Again, his magic is in seat increase and constituency redelineation.

The Election Commission under Tan Sri Abdul Rashid Abdul Rahman helped him with an increase of 26 seats in the Peninsula and Sabah (including Labuan) in 2003.

In 1995, Mahathir’s BN won 65.27% of votes in these two regions, which was translated into 82.42% of their total seats, yielding a vote value of 126%. By 2004, Abdullah’s BN won 90.05% of seats with 63.72% of votes, yielding a vote value of 1.41.

READ MORE HERE

No comments:

Post a Comment